Robot Program Parameter Inference via Differentiable Shadow Program Inversion

This is the companion blog post to our 2021 ICRA paper. You can find more on the paper (including a full-text version) here.

Programming industrial robots to perform complex force-controlled tasks is challenging and time-consuming when done by hand. Skill-based robot programming is an established paradigm across industrial and service robotics, where commonly used robot actions are encapsulated as robot skills which must only be learned or programmed once and can then be reused or combined to higher-level skills. This makes the creation of an initial robot program much easier, but leaves the problem of skill parameterization: For each skill in a program, the robot programmer must find a suitable set of parameters to adapt that skill to the concrete task and environment at hand.

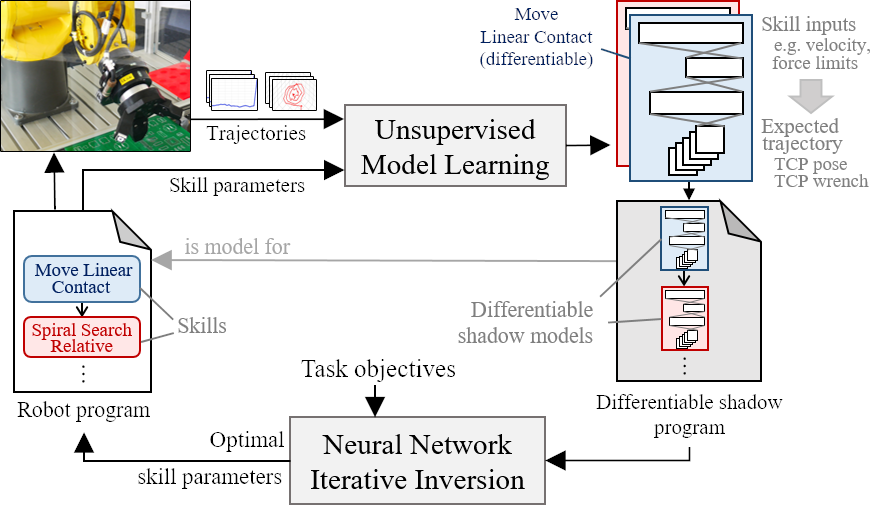

In our paper, we present Shadow Program Inversion (SPI), a novel approach to infer optimal skill parameters directly from data. SPI leverages unsupervised learning to train an auxiliary differentiable program representation (“shadow program”) and realizes parameter inference via gradient-based model inversion. Our method enables the use of efficient first-order optimizers to infer optimal parameters for originally non-differentiable skills, including many skill variants currently used in production. SPI zero-shot generalizes across task objectives, meaning that shadow programs do not need to be retrained to infer parameters for different task variants.

This brings the benefits of differentiable programming (\(\partial P\)) - the possibility to optimize program parameters with gradient-based optimizers such as Stochastic Gradient Descent - to skill-based robot programming.

Core Idea: Splitting the Optimization Problem

Optimizing program parameters is hard: Typically, the space of possible values is high-dimensional (programs can have arbitrarily many parameters) and continuous (most program parameters, such as target forces or grasp points, are real-valued). Iterative gradient-free optimizers such as Evolutionary Algorithms require the repeated execution of the program with candidate parameters (to determine e.g. the fitness value), which is very time-consuming and potentially dangerous in production environments. Supervised learning (i.e. training a neural network to directly compute the optimal parameters \(x^*\)) requires labelled training data, which implies that the optimal parameters would have to be known in advance - eliminating the need for optimization in the first place.

To make parameter optimization tractable, we use a model-based approach and split the hard problem of optimizing program parameters into the much easier problem of first learning a model of the program (a mapping from program inputs to outputs, i.e. robot trajectories), which we design to be easily invertible, and then inverting that model to obtain the optimal inputs. In other words, we turn a hard inverse problem into an easy forward problem and an easy inverse problem.

The Forward Problem: Model Learning

Unlike optimizing program parameters, learning a forward model of a robot program only requires input-output training tuples \((x, Y)\), which can be collected by simply observing what the robot does when the program is given inputs \(x\). Crucially, the optimal parameters don’t need to be known. Data can be collected in an entirely unsupervised fashion, by randomly sampling \(x\) and observing the resulting trajectories \(Y\). In industrial scenarios, this enables the efficient use of existing robot data, collected and persisted e.g. by IIoT platforms.

The Inverse Problem: Parameter Optimization

By design, the learned models are fully differentiable (see Shadow Skills). This allows for the use of gradient-based optimizers to effectively invert the model: To compute the set of parameters \(x^*\) which maximize some user objective \(\mathcal{G}({Y})\) over the robot trajectory. We do this by iterative gradient descent in the input space of the model - we iteratively use our model to predict \(Y\), evaluate \(\mathcal{G}({Y})\) and use PyTorch’s Autograd engine to compute gradients \(\frac{\partial{\mathcal{L}(Y)}}{\partial{x}}\), which we use to nudge \(x\) toward maximizing \(\mathcal{G}({Y})\).

By eschewing direct optimization of the parameters in favor of learning a differentiable model of the program and performing parameter optimization via gradient descent over its input space, the joint optimization of very large numbers of program parameters becomes tractable without requiring labelled training data, supervised learning or reinforcement learning.

Shadow Skills

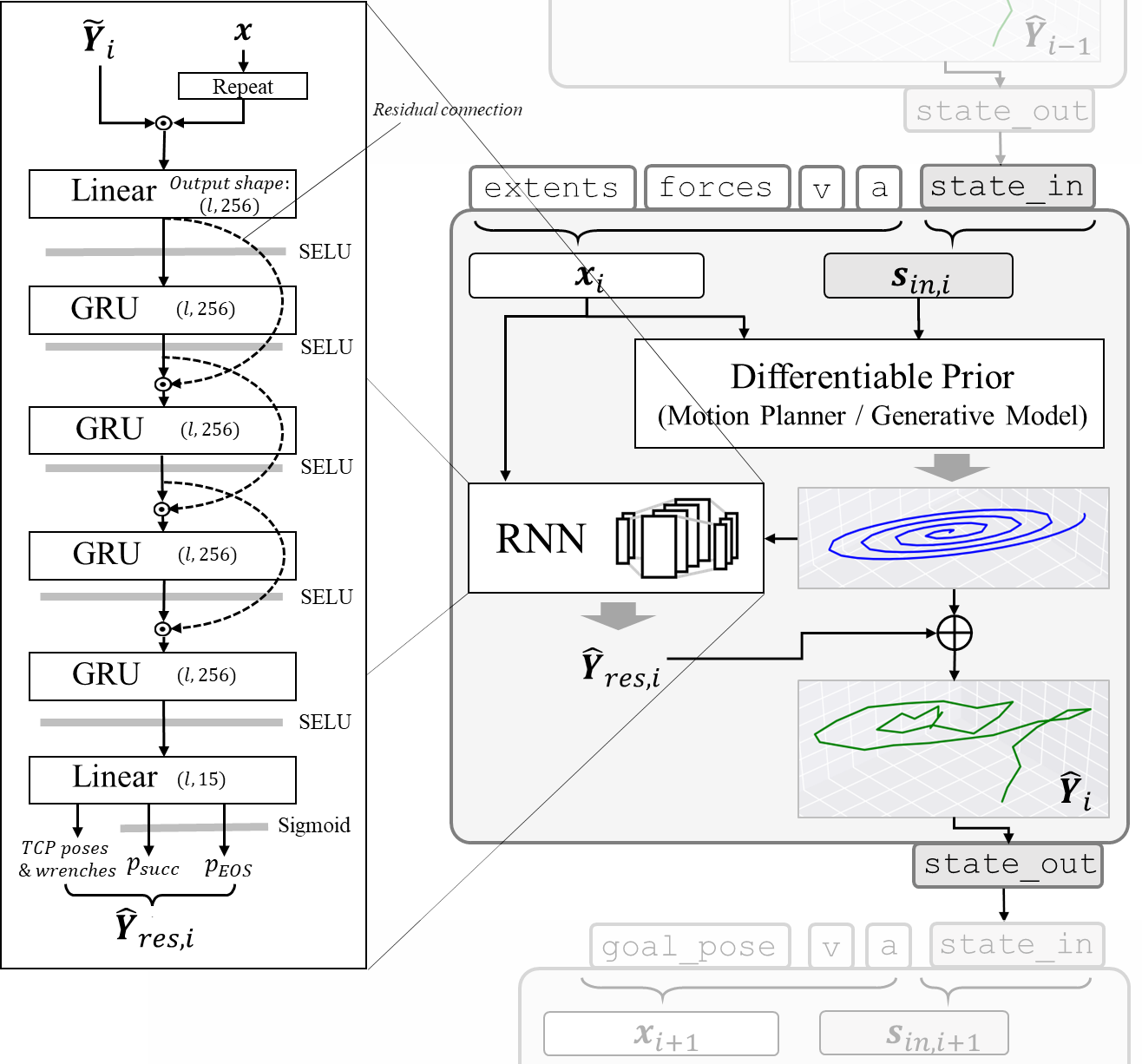

Our learnable forward model of robot programs is highly modular and composable, reflecting both the innate structure of most tasks and the typical hierarchical structure of most robot programming frameworks. A general-purpose differentiable and “shadow skill” architecture must meet three general requirements:

- It must be implementation-agnostic with respect to the skill it represents, i.e. it must be capable of accurately representing possibly non-differentiable robot skills, and even hand-written skills in a low-level robot programming language such as KRL or URScript.

- It must have a learnable component which can learn the non-deterministic aspects of skills, such as the forces and torques resulting from interactions with the environment.

- It must be chainable to represent complex robot programs composed of multiple skills.

To meet these requirements, we designed a hybrid robot skill architecture which combines a differentiable motion planner (an implementation of a motion planner in a \(\partial P\) framework such as PyTorch) with a recurrent neural network, and wrap both components in a differentiable computational graph. The combination of a differentiable implementation of a traditional planner with a trainable neural network permits the architecture to represent a wide variety of skills, including complex force-controlled skills, in a data-efficient way. Echoing recent related work, we find that the explicit inclusion of domain knowledge in the form of an algorithmic prior greatly reduces the amount of data and compute required to learn complex skills.

To the outside, every shadow skill provides the same interface: All skills accept a parameter vector \(x\) containing the skill parameters (which we want to optimize) and a state vector \(s_{in}\) describing the current state of the robot and the environment, and produce an expected trajectory \(\hat{Y}\) and a final state \(s_{out}\). Because both the differentiable motion planner and the neural network are differentiable computational graphs, a shadow skill is also a differentiable computational graph whose outputs \(\hat{Y}\) and \(s_{out}\) are differentiable w.r.t. its inputs \(x\), conditional on the initial state \(s_{in}\).

This skill architecture can be used to learn new skills from scratch (e.g. from human demonstrations), but its most useful application is modeling existing skills from different frameworks. There are many existing, highly expressive robot program representations which are used in production. Some of them are highly domain-specific (e.g. optimized for welding applications), others are hardware-specific (e.g. the KRL or URScript textual programming languages), and yet others are based on differential equations (DMPs, ProMPs and variants). Our architecture is designed with the aim of being capable of learning to model skills from any such framework or language. Instead of forcing robot programmers to program their robots a priori in a differentiable language, we designed our skill architecture to be sufficiently flexible to learn the execution semantics (input-output relationships, “what happens when the skill is executed”) of any existing skill from any skill framework or robot programming language.

Training a Shadow Skill for an existing robot skill is easy: Simply sample skill inputs \(x\), observe the resulting robot trajectories \(Y\) and train the learnable Shadow Skill components (namely, the RNN) to predict \(Y\) given \(x\).

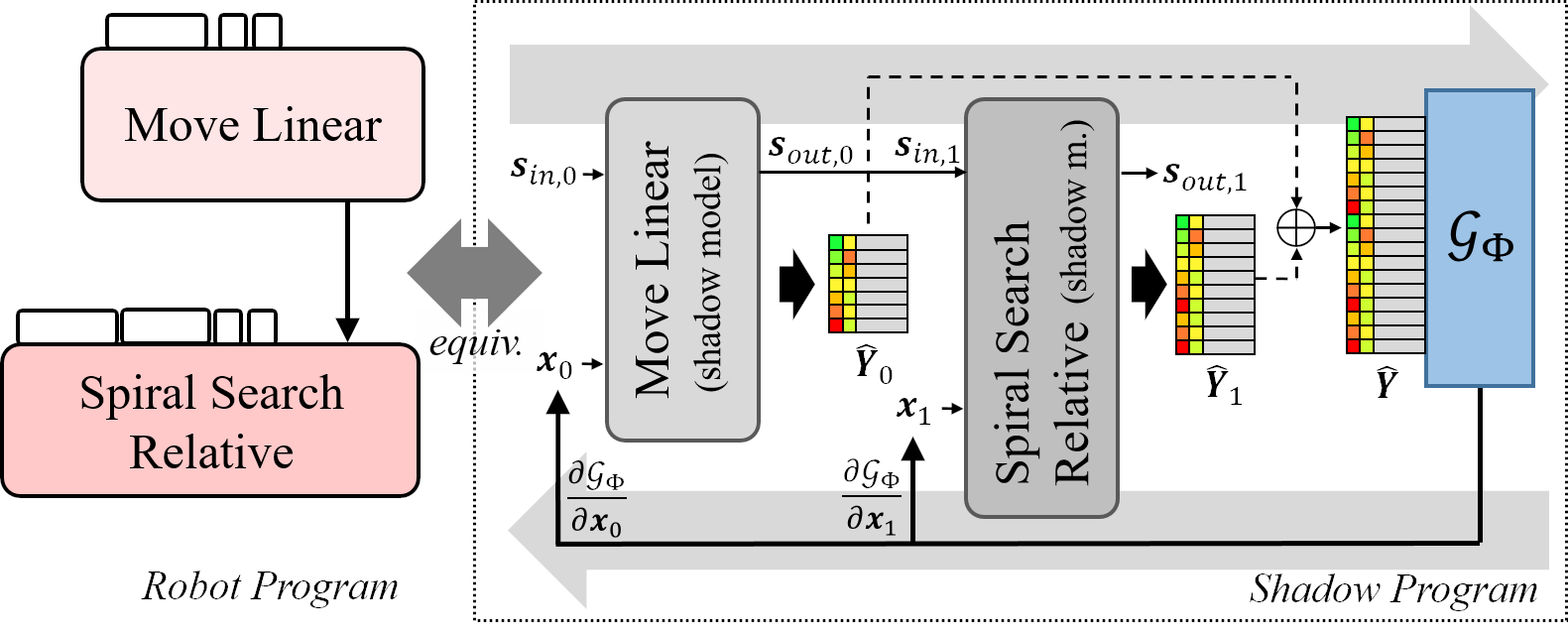

Shadow Programs

While our framework can be used to infer optimal parameters for individual robot skills, many real-world applications require the combination of several skills to achieve more complex goals. To take a cookie out of a jar, for instance, a robot must first open the jar, grasp the cookie and remove the cookie from the jar. To open the jar, the robot must in turn open its gripper, approach the lid, close its gripper around the lid, twist the lid and depart, etc. Most real-world tasks are intrinsically hierarchical and can be broken down into sequences of primitive actions. Consequently, most robot programming frameworks are themselves hierarchical, and allow the composition of complex tasks from sequences of primitive skills. By extension, optimizing the parameters of a robot program requires the joint optimization of the parameters of its constituent skills: The values of skill parameters at the beginning of the program cause changes to the state of the world and the robot, which may influence the optimal parameter values later in the program.

End-to-end learning addresses this by learning one large model for the entire program. In practice this is not tractable, as learning to model highly complex programs requires substantial computing power and amounts of training data far in excess of what can be collected on real robots in industrial settings. We propose to train individual Shadow Skills in isolation, and to combine them afterward to complex programs. Training Shadow Skills in isolation allows for the building of a trained skill library, which only needs to be done once, and skills don’t need to be re-trained to be combined into new programs. If you are a robot programmer and want to optimize your program parameters, this is great news: You only need to train one Shadow Skill for each skill in your skill library, and are instantly able to optimize the parameters of any program you can compose.1

Because the individual Shadow Skills are forward models of robot skills, their combination to a Shadow Program constitutes a forward model of a robot program. Just as Shadow Skills are differentiable computation graphs, a Shadow Model is a differentiable computation graph. Via gradient descent in the input space, the parameters of all skills in the program can be jointly optimized w.r.t. some function of the expected behavior of the robot, such as cycle time, parts per minute (PPM) or the forces experienced on contact with an object.

Applications

We applied SPI to several very different parameter inference problems in industrial and service robotics. In one experiment, we inferred the parameters of an robot program in the ArtiMinds ARTM programming language to pick up a glass and deposit it in a sink from a single human demonstration in Virtual Reality (VR). In other experiments, we use SPI to optimize the parameters of ARTM programs, URScript programs and DMPs for force-sensitive contact motions with materials of different spring and damping characteristics. In a final experiment, we optimize the parameters of force-controlled spiral search motions to find the position of a hole on a PCB quickly, robustly or efficiently, respectively. Our experiments indicate that SPI is a highly versatile alternative to end-to-end supervised or reinforcement learning, particularly in industrial settings, as it is capable to infer optimal parameters for any existing programming framework ranging from textual programming languages like URScript to symbolic representations like ARTM or subsymbolic skill representations like DMPs. By learning an auxiliary representation (the Shadow Skills) for optimization, SPI can retrofit these established robot programming frameworks which are widely used (but neither differentiable nor learnable) with differentiable programming, and by extension learning and gradient-based optimization. This property is crucial for real-world application in the industry, as robot programmers can continue using the languages they know and like, without foregoing the benefits of differentiability and learning.

-

One caveat is that robot skills typically cannot be learned independent from the state of the world (such as the positions of objects in the environment) at the time of their execution. This implies that some fine-tuning on the current state of the world will be required, at least when skills (or programs) are transferred from one environment to another. We are currently investigating methods to do this efficiently. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: