KRROOD: Knowledge Representation and Reasoning with Object Oriented Design

TLDR: KRROOD is an open-source Python framework that makes knowledge representation and reasoning feel like regular object-oriented programming (ArXiv , PDF ).

Neurosymbolic systems have long been identified as promising architectural alternatives to monolithic end-to-end systems. Particularly in physical AI, systems that combine deep, neural architectures with symbolic representations and reasoning methods could bring about forms of intelligence that is safer, more interpretable and possibly more capable than purely subsymbolic architectures. While the programming infrastructure around neural architectures and leanring frameworks has seen explosive growth and tremendous improvements over the last few years, the software infrastructure around symbolic knowledge and inference has not kept pace, learning to a situation in which integration of multi-billion-parameter Transformer architectures is possible in a few lines of code, while defining a knowledge graph with only a few entities and axioms is weirdly difficulty. We recently developed a new open-source framework to address this challenge, and make symbolic knowledge representation and reasoning more accessible to programmers of neurosymbolic AI systems.

- Logic Programming

- Building Hybrid AI Applications

- KRROOD: Making Symbolic AI Feel Like Python

- Performance Evaluation

- When to Use KRROOD

- Getting Started

- Citing KRROOD

Logic Programming

The Good

Neurosymbolic AI is an active field of research with many fundamental, challenging research questions. On the practical, implementation side, there is another fundamental challenge: How can AI system developers actually leverage symbolic representations? When first entering the field of neurosymbolic AI, I was struck with how archaic the development environment felt. I (or rather, the symbolic part of my intellectual work) was embedded in the tradition of Prolog and rules-based reasoning systems. Prolog realizes an amazing and unique programming paradigm: Declarative logic programming allows developers to write down what the world is like, in terms of if-this-then-that statements. A Prolog predicate is a statement about the world. Executing a Prolog “program” - it never feels like a program, but rather like a knowlede base - means unifying unbound variables with the available knowledge. Prolog does this automatically under the hood, and the programmer gets bindings for all variables that make the set of statements true, given the knowledge base - or the Prolog prompt outputs false, in which the dream of declarative progamming and execution-as-inference collapses.

The Bad

Prolog outputting false means that there is no binding, no set of values, for the variables that make the active set of Prolog statements true. This is indicative of one of three cases: Either (a) there really is no such set of values, and the solution to the problem that the Prolog program was written for cannot be derived from the knowledge base; or (b) there is a bug in your program that will make Prolog return false in most cases, regardless of what is in the knowledge base; or (c) there are conflicting facats in the knowlede base. The frustration with logic programming in Prolog is that it is extremely difficult to tell which of these is the case.

The Ugly

Debugging Prolog applications is wickedly hard. There is no good IDE support, and no built-in type system to syntactically declare what type a variable used in a predicate signature is expected to be. The declarative nature of Prolog programs, while arguably their greatest advantage, also hides the order of operations from the programmer, who must emulate the unification algorithm in their head in order to understand where inconsistencies arise. Because declarative languages hide the order of operations from the programmer, a good debugger is key, in order to trace through the inference mechanism as inference is performed. The debugging ecosystem in Prolog, however, is extremely difficult to use, and there are no integrations into modern IDEs that make that process easier. While logic proramming in Prolog can feel extremely powerful, those advantages were overwhelmed by the sheer difficulty of maintaining and debugging large-scale, real-world, intelligent systems with the available developer tools.

Building Hybrid AI Applications

Building hybrid AI applications is difficult, not just because of the large design space of possible neurosymbolic representations and algorithms and the lack of tool support around symbolic programming, but also due to the fact that symbolic and subsymbolic system components “live in different worlds” from a software engineering perspective. I noticed this strongly when implementing neurosymbolic robot program representations and the programming interfaces and execution systems around them: Whenever reasoning (in the KR&R sense, not the LLM sense) or the specification of symbolic knowledge was required, I had to use representations and toolchains fundamentally different from those in which I built the neural system components. For specifying knowledge, I was using OWL (for ontological knowledge) or PDDL (for the specification of planning problems). For reasoning on that knowledge, I used Prolog, while the rest of the applications, including learning, optimization, robot control and user interaction, were built in Python. This created friction both in terms of representation and in terms of tooling, which created an artificial separation between ontological knowledge, reasoning routines operating on that knowledge, and the rest of the application that actually controls the robot and interacts with the user. This object-ontological impedance mismatch, the representational gap between knowledge and application logic, has been confronting developers of hybrid AI systems since the inception of the field. It is analogous to the object-relational impedance mismatch in database programming, and stems from the fact that object-oriented programming (OOP) and logic programming make fundamentally different assumptions about completeness (closed-world vs. open-world) and program semantics (declarative vs. procedural). From an AI application programmer’s perspective, whose objective is to solve a complex real-world problem, this mismatch is evident in the tooling landscape: Ontological knowledge is expressed in OWL and constrained to the expressiveness of OWL, reasoning is done with OWL reasoners and restricted to the feature set and performance characteristics of those reasoners, logic programming is done in logic programming languages and frameworks, and all of the rest of the application, including AI agent integration and the robot control backend, are written in Python.

As a roboticist, I want to build systems that can competently and safely act in the real world. The current tooling ecosystem around programming with knowledge made this extremely difficult, and forced me to spend much more time on getting the implementation to work, rather than solving the thorny learning and inference problems that are actually interesting. I want a knowledge programming system that just works.

KRROOD: Making Symbolic AI Feel Like Python

KRROOD is an attempt to make knowledge representation and reasoning natively available in Python. I didn’t come up with KRROOD, nor did I implement it. Two brilliant colleagues, Tom Schierenbeck and Abdelrhman Bassiouny at University of Bremen, pitched me the idea, and I helped them turn it into a scientific project and publication. The framework is now open source and ready to use.

Links:

-

Paper: - Code: GitHub

- Documentation: https://code-iai.github.io/krrood/intro.html

Authors: Abdelrhman Bassiouny, Tom Schierenbeck, Sorin Arion, Benjamin Alt, Naren Vasantakumaar, Giang Nguyen, Michael Beetz Institution: AICOR Institute for Artificial Intelligence, University of Bremen, Germany

Core Idea: Knowledge as Python Objects

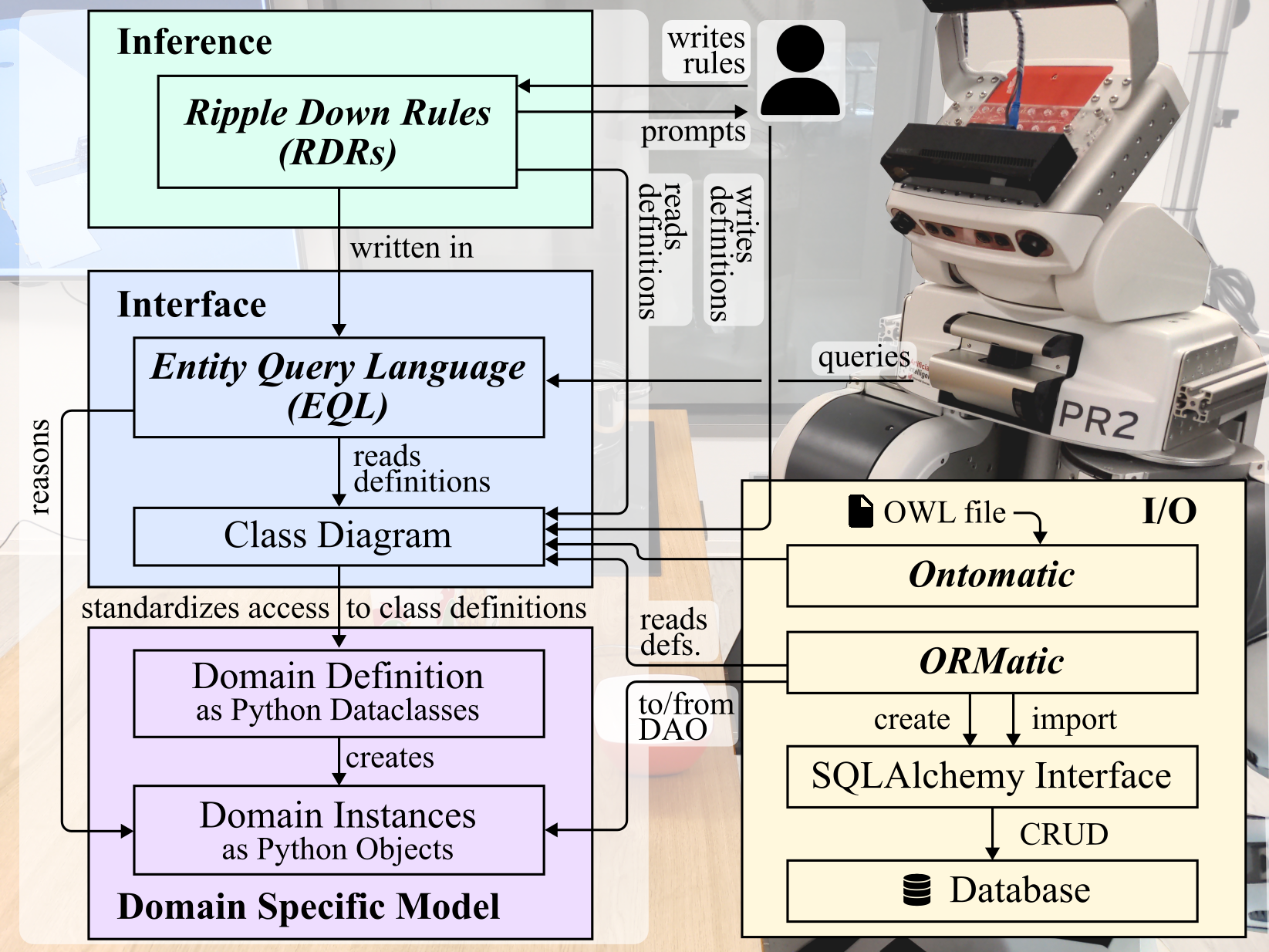

KRROOD’s central design principle is treating knowledge as a first-class programming abstraction rather than an external resource. Instead of maintaining separate ontology files and invoking external reasoners, domain knowledge is represented using Python dataclasses and type annotations. This allows application developers to define rules and reasoning mechanisms over the same objects that form part of their application, and allow deep integration of symbolic reasoning into hybrid AI systems.

KRROOD provides five components that work together to enable native KR&R in Python:

Object-Oriented Knowledge Representation

Python dataclasses serve as the foundation for defining domain ontologies. Consider this example from the OWL2Bench benchmark, where a LeisureStudent is defined as a student who takes at most one course:

class LeisureStudent(Student):

@classmethod

def axiom(cls, candidate):

return (

exists(IsSubClassOrRole(candidate.types, Student)),

HasProperty(candidate, TakesCourse),

count(IsSubClassOrRole(candidate.takes_course.types,

Course)) <= 1

)

KRROOD allows to define axioms using qualifiers, properties and other logic constructs on domain objects (like Student). axioms can be used for validation, classification, or any other reasoning task that requires checking constraints. Other mechanisms for natively modeling knowledge in Python are documented here.

Entity Query Language (EQL)

EQL is a declarative query language grounded in conjunctive query semantics, extended with union, negation-as-failure, and restricted universal quantification over the active domain. Unlinke classical first-order logic, EQL assumes closed-world semantics. This reflects the needs of physical AI systems that can only act on the world as it has been perceived by their sensor. Unlike SQL or SPARQL, EQL operates directly on Python objects and is implemented entirely in Python.

The following simple query finds all persons aged 20:

p = variable(Person)

query = an(entity(p).where(p.age == 20))

A more complex query finds all robots with a given set of capabilities and kinematic properties:

query = a(set_of(robot, capability).where(

contains(robot.capabilities, capability),

robot.parts.size[0] <= 1,

for_all(arm, count(arm.fingers) == 5)))

In EQL, variables represent symbolic constraints over sets of values. The where clause supports conjunctive conditions, nested quantification, and direct access to object attributes. Crucially, variables can be constructed from domains computed at runtime, enabling queries over procedurally generated sets. EQL is documented in detail here.

Ripple Down Rules (RDRs)

RDRs provide incremental maintenance of conflict-free rule sets and allow human experts to interactively build up complex rule trees. The rule trees are built incrementally as conflicts arise, and enable a form of active learning, in which the knowledge system automatically asks for clarifications if it detects (or learns) conflicting rules. This is particularly useful in domains such as robotics, in which AI systems must constantly draw conclusions and update beliefs from noisy sensory inputs, and require robust rule sets that will invariably lead to conflict. Conflicting rules are one of the main things that make logic programming in e.g. Prolog so hard, and it is generally preferable to have a knowledge representation system that detects conflicting rules and asks for clarifications rather than just returning false.

Consider the following example:

fixed_connection = variable(FixedConnection)

child = fixed_connection.child

parent = fixed_connection.parent

with HasType(child, Handle):

Add(inference(Drawer)(container=parent))

with refinement(parent.size > 1):

Add(inference(Door)(body=parent))

The base rule states that when a FixedConnection has a Handle as its child body, the parent body should be classified as a Drawer. This initial inference works for many cases, such as cabinets with drawer handles.

We don’t initially model that doors, like drawers, also have handles - and it is generally neither possible nor desirable to model every possible fact about the world a priori. RDRs allow the system to encounter a door with a handle and trigger a rule violation. A human expert is asked to provide a distinguishing condition that Doors have body sizes greater than 1 meter, while Drawers are typically smaller. The refinement clause captures this exception. When the parent body size exceeds 1m, the exception rule fires and overrides the base classification, correctly inferring a Door instead.

Rule conditions can be arbitrary Python code, enabling direct use of geometric reasoning, physics simulation, or domain-specific APIs.

ORMatic

ORMatic is KRROOD’s ORM generator. It generates SQLAlchemy interfaces from Python dataclasses and provides transparent persistence without requiring separate schema definitions. Unlike traditional ORMs that force domain objects to handle their own persistence and violate the Single Responsibility Principle, ORMatic maintains clean separation between domain logic and storage through Data Access Objects (DAOs).

The system ensures the domain model and data schema remain identical, eliminating synchronization errors and reducing cognitive load.

Ontomatic

Ontomatic converts OWL ontologies into object-oriented Python structures in two phases:

- T-Box conversion: Generates classes from concepts, infers subsumption hierarchies, converts property domains/ranges, and encodes OWL axioms as EQL predicates.

- A-Box loading: Instantiates individuals with appropriate types inferred from declarations, properties, and class axioms.

One challenge in building Ontomatic was that OWL allows non-disjoint sibling classes (an individual can belong to multiple siblings simultaneously), which conflicts with single-inheritance OOP. Ontomatic resolves this using the Role pattern: a persistent entity represents identity (URI), while role-specific classes reference it via composition. This aligns with OntoClean modeling principles and allows individuals to assume multiple roles concurrently.

Performance Evaluation

We evaluated KRROOD on the OWL2Bench benchmark (OWL 2 RL profile) with 54,897 raw statements, expanding to 1,502,966 statements after reasoning.

Loading and Reasoning Performance

| Framework | Raw Data (s) | Reasoned Data (s) | Memory Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| KRROOD | 8.3 | 127.9 | Orders of magnitude more memory-efficient than OWL alternatives |

| Protégé + Pellet | 5.5 | 22.0 | Fastest but requires ~5GB reasoning, 25GB export |

| GraphDB (OWL RL) | 1820 | 1606 | Most reliable for large-scale; stable memory |

| owlready2 + Pellet | 203.9 | Out of memory | Memory exhaustion on reasoned data |

| RDFlib + owlrl | 36.0 | >10800 | Failed to terminate within 3 hours |

Key findings:

- KRROOD achieves competitive reasoning performance (8.3s raw, 127.9s reasoned) while providing native integration with application logic

- Protégé is fastest but has severe memory constraints limiting scalability

- GraphDB is the most reliable alternative for large-scale reasoning but lacks native object integration

Query Performance

We measured execution times for all queries in the OWL 2 RL profile. Results show geometric mean across queries:

| Framework | Geom. Mean (ms) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SQLAlchemy | 3.39 | Pure relational; no domain objects |

| GraphDB | 8.07 | Viable alternative when query speed is |

| KRROOD (EQL) | 19.72 | Fully capable domain objects for native integration |

| RDFlib | 26.45 | |

| owlready2 | 49.82 | |

| Protégé | 78.33 | Failed to terminate on one query |

Key findings:

KRROOD with EQL provides fully capable domain objects while maintaining query performance within 2.4× of GraphDB and 5.8× of raw SQL, both of which are extremely fast. The query performance of KRROOD is ~2x faster than that of owlready2, which is the current standard for Python-based knowledge programming. For applications that require runtime introspection, procedural reasoning or tight coupling between knowledge and domain behavior, this trade-off is appropriate.

For large-scale queries where domain objects aren’t needed, applications can use SQLAlchemy directly on KRROOD’s persisted data, achieving best-in-class performance.

Robot Task Learning Validation

We validated KRROOD in a human-robot interactive task learning scenario implemented in the Multiverse multi-simulation framework with a VR interface. A human demonstrates object insertion tasks using a Montessori box, and the robot learns to insert the correct objects into the correct holes through corrective demonstrations.

The system uses KRROOD’s RDR trees to incrementally learn inference rules for event annotation (e.g., detecting PickUpEvents, FallingEvents and other semantic environment interactions from physics-enabled VR demonstrations) and task constraints (e.g., which objects fit which holes). When the robot makes an error, it requests a corrective demonstration, and automatically refines its rule tree.

When to Use KRROOD

KRROOD is designed for applications where:

- Knowledge must be tightly integrated with application logic (robotics, interactive systems)

- Runtime introspection and explanation are required

- Incremental learning from expert feedback is possible and/or necessary

- Development in pure Python without external reasoner dependencies is preferred

- The domain operates under closed-world assumptions.

KRROOD may not be suitable when:

- You need open-world reasoning with complete OWL-DL semantics

- Hard real-time guarantees are required

- The application is purely batch processing over static knowledge bases

- Performance is the sole concern and domain objects are unnecessary. In these cases, direct access to e.g. GraphDB or raw SQL is preferable.

Getting Started

Install KRROOD from PyPI:

pip install krrood

Define domain knowledge using Python dataclasses:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from krrood import variable, entity, an

@dataclass

class Person:

name: str

age: int

# Create instances

alice = Person("Alice", 25)

bob = Person("Bob", 30)

# Query using EQL

p = variable(Person)

adults = an(entity(p).where(p.age >= 18))

Citing KRROOD

@misc{bassiouny2026krrood,

title={Implementing Knowledge Representation and Reasoning with Object Oriented Design},

author={Bassiouny, Abdelrhman and Schierenbeck, Tom and Arion, Sorin and Alt, Benjamin and Vasantakumaar, Naren and Nguyen, Giang and Beetz, Michael},

year={2026},

eprint={2601.14840},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.AI},

institution={AICOR Institute for Artificial Intelligence, University of Bremen}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: